Bob and I have been watching a lot of "Ryoori no Tetsujin" lately. That's Iron Chef to you. It's not on the air anymore but many of the episodes are on Youtube, including some fantastic ones on milk, natto (fermented soybeans,) and umeboshi (pickled Japanese plums.) I started to play Iron Chef in my own kitchen, trying to come up with "original dishes that can truly be called works of art." I'm afraid, though, that my creativity is severely lacking compared to anything the Japanese pizza companies can dream up.

I like to read the ads that come through my mail slot purely for humor value. I've never ordered a pizza here, at least not for delivery. Dominos and Pizza Hut do exist here and I think they do a pretty brisk business (pizzas cost 18-30 bucks a pop, so I think they must be making money.) Papa John's is still limited to South Korea, sadly. If any Papa John's authorities are reading this now- GET OVER HERE!

But do not think that the pizzas here are the same as your precious American Dominos. No no no. It has all been reenvisioned, repackaged and renamed for the Japanese consumer. They have the fairly normal ones like Margherita, Pepperoni and Mozzarella, and the "American Special." None of these are on the top 3 "Most Popular" list or the 5 "Children's Favorites." No, to understand what makes a Japanese pizza, you need to go back to the very foundation of pizza. First, take the crust. Crust can be either regular, thin, mille-feuille (kinda like puff pastry, with many layers), or double mille-feuille (that means two thousand layers!) Camembert cheese often makes an appearance, layered between two crusts or sneaking in between the sauce and the mozzarella cheese. Moving on to the sauce- normal tomato sauce is used on about half of all pizzas, and pesto maybe once or twice. But the rest feature bolognese sauce, chili sauce, teriyaki sauce, curry sauce, SPICY FISH EGG SAUCE, and the vaguely named "white sauce."

I cannot even begin to describe toppings to you other than to say: Potatoes. Corn. Mayonnaise. Scallops. Anything goes. And this is at one of the more Americanized pizza chains. Expect seaweed, cauliflower, canned tuna and fried glutinous rice at the homegrown chains. Yes, you can order a la carte toppings, on a normal cheese pizza, but the instructions for doing so take up about a 1-inch width at the bottom of the 2-page menu spread. It seems that is not done here. The pizza topping that sticks up must be hammered down. I will give Japan points for one thing- pizza technology, it seems, has advanced further than in America, and pizzas can not only be divided into halves but QUARTERS. With radically different toppings. And no tipping your delivery guy!

So now with a bit of background, you understand how bizarre pizzas can get. But even knowing all this, and feeling quite original lately in the kitchen, I was gobsmacked when I got the Dominos ad today. Yes- they have figured out a way to combine STEW and PIZZA. Their new "Cheese Ristorante" line of pizzas has 2 options. You can get the Truffled Beef Stew: a pizza crust, smothered with the aforementioned beef stew, covered in mozzarella cheese, and for the finishing touch, dollops of whipped cream cheese adorn the edges like the numbers on a clock.

Perhaps the Tomato Cream and Crab sounds better. It's similar to the above but instead of stew the crust is topped with a tomato cream sauce, crab meat, and broccoli. That is then covered with mozzarella cheese and artistically arranged Camembert cheese. (I don't get it with the Camembert here.) I wish I had a scanner so I could show you the scientific-looking cross sections of pizza, on page 3 of the ad. Oh, and by the way, these cost 4500 yen each, which right now is about $40 or $42. Just can't decide which one to get? Simple! You can order the Half and Half, and try them both. Honestly, if I had my whole life to do it, I don't think I could have ever come up with such a pizza. Bob told me, "That's why you're not the Iron Chef." That's true. Once again, the Japanese Dominos has astounded me with their creativity. I'm not sure why they were never on Iron Chef- though I have a sneaking suspicion that they'd get all points for originality and none for taste. All I know is, I don't want to be eating that middle piece where the stew and crab cream blended together.

Saturday, December 6, 2008

Wednesday, September 10, 2008

Book Report

Have you read Barbara Kingsolver's new book, Animal, Vegetable, Miracle? If you haven't, go read it. NOW.

You're back? Good. I would be a little ashamed to tell you just how much I learned from that book. I should have known, for instance, how potatoes grow, or how to store things like tomatoes and zucchini when the season is over. (Just freeze them whole, apparently.) Thanks to a summer working in a grocery store, I know when the different summer crops come into season, and how to pick the best fruits or vegetables off the store shelf. Even cantaloupes. And since starting our little garden out back, I've learned quite a lot more. I thought that if I had to start producing a majority of my own food, I could do it. That's what Kingsolver and her family did, for a whole year. The premise appealed to me (though I'm certainly not going to try it anytime soon, my backyard isn't that big) from a gardener's standpoint. Since moving to Japan, I've become interested in growing my own food, since I have the space to do it, it's cheaper, and it's healthier (I don't use pesticides.) I started off with some tomatoes, recalling summers at home spent eating delicious homegrown tomatoes. I added bell peppers, which tend to be expensive here. It snowballed from there. For the winter, we're planting onions, garlic, potatoes, and spinach. Now it's less about the money aspect- I can afford all the onions and potatoes I want. It's more about having that homegrown taste, and lessening my impact on the environment.

I've started reading labels in the grocery store on almost every item I buy. I bought lemons last week. There were two types; each cost about $1. One was imported from Chile, the other two prefectures away in Hiroshima. I don't have any statistics for you, but just think about it: how much fuel did it take to get that fresh lemon from Chile to Japan, keeping it cold the whole way? And how much fuel did it require to get from Hiroshima to my street (a distance of, I don't know, about 150 miles.) It's obvious which choice is better for the environment. I'm not sure why everyone isn't complaining about this, since we sure do enough complaining when it comes to filling up our gas tanks. And we're paying for it- if you're not paying for it at the cash register, you're paying when you pay your taxes, since farms (of any size, I believe) can deduct their transportation expenses. The average item on your grocery store shelf probably traveled farther than you did on your summer vacation this year, according to Animal, Vegetable, Miracle.

The other amazing thing to me is that these lemons cost EXACTLY the same amount, despite the wide difference in cost in getting to my local MaxValu. So which farmer will be getting more of my money? Guess. Which lemon did I buy? That's right.

Being in Japan has made me more aware of things like seasonality and local crops. While the Japanese, like Americans, enjoy the luxury of having everything, all the time, for the most part foods are enjoyed only when they're in season. I have recipe cards that tell me what season I should cook each dish in. At first I thought it was silly, I had a mentality of "I can eat onion soup whenever I want!" and so on. But it makes sense, considering our living situation. In February, no Japanese person would say "Oh, I just want something light tonight, like a salad" and then complain about being cold and turn up the heat to 80 degrees. Because you can't. It is 40 degrees indoors, there is no central heat, and if you don't plan on freezing while you sleep, you had better eat some stew for dinner. I'm not saying it's perfect. If I had the choice, I'd go for the central heat, without a doubt. But I'd make sure to eat lots of stew and take lots of baths in the winter, to save some money and help the environment too.

The Japanese also firmly believe in local specialties, another concept I thought was dumb at first. Just about every city has something they are famous for. A city near me, Akashi, is famous for its particular style of grilled octopus balls (they dip them in broth) and there are countless different types of noodles. Every bag of rice is clearly labeled with its area of origin. People travel to Hokkaido just to try the fresh crabs. To me, it seemed silly, because couldn't anyone make some broth for their octopus balls? Well, they could, but Akasahi is on the Japanese Inland Sea, and they probably use some sort of local seaweed that tastes different from the seaweed that grows near Okinawa or Tokyo. It's widely accepted that wines grown in different regions or even different counties will taste different. Why not food? When I ate crab in Hokkaido this summer, it tasted fresher than any other crab I've had here. There's no substitute for it. When I returned from Hokkaido, my coworker asked me these questions, in order:

Her: Welcome back! Did you have a good trip?

Me: Yes, it was very relaxing.

Her: Did you eat jingus kan? (grilled mutton on sticks, a famous Sapporo dish)

Me: No, but I ate a lot of ramen. (Sapporo is also famous for its style of ramen.)

Her: How about crab?

And so on. And don't forget the number one most important thing of Japanese vacations-- you must bring back o-miyage, or souvenirs. This is ALWAYS food. The idea is that you should bring back some local food for all your coworkers to sample. From various vacations, I have brought back chocolates, chips made out of bitter gourds, fruit-flavored cookies, tofu cookies, bean-filled dumplings, buckwheat pancakes, and so on.

I think that if Barbara Kingsolver were to come to Japan, she would be disappointed that Japanese mothers do not "take the time to roll out the sushi by hand," as she suggests in her book. The only people I know who make sushi are sushi chefs, and no, even in Japan, there is no such thing as a "sushi machine." But she would be pleased to find a- dare I say it?- UNIQUE food culture that is built entirely upon eating local food, in season.

You're back? Good. I would be a little ashamed to tell you just how much I learned from that book. I should have known, for instance, how potatoes grow, or how to store things like tomatoes and zucchini when the season is over. (Just freeze them whole, apparently.) Thanks to a summer working in a grocery store, I know when the different summer crops come into season, and how to pick the best fruits or vegetables off the store shelf. Even cantaloupes. And since starting our little garden out back, I've learned quite a lot more. I thought that if I had to start producing a majority of my own food, I could do it. That's what Kingsolver and her family did, for a whole year. The premise appealed to me (though I'm certainly not going to try it anytime soon, my backyard isn't that big) from a gardener's standpoint. Since moving to Japan, I've become interested in growing my own food, since I have the space to do it, it's cheaper, and it's healthier (I don't use pesticides.) I started off with some tomatoes, recalling summers at home spent eating delicious homegrown tomatoes. I added bell peppers, which tend to be expensive here. It snowballed from there. For the winter, we're planting onions, garlic, potatoes, and spinach. Now it's less about the money aspect- I can afford all the onions and potatoes I want. It's more about having that homegrown taste, and lessening my impact on the environment.

I've started reading labels in the grocery store on almost every item I buy. I bought lemons last week. There were two types; each cost about $1. One was imported from Chile, the other two prefectures away in Hiroshima. I don't have any statistics for you, but just think about it: how much fuel did it take to get that fresh lemon from Chile to Japan, keeping it cold the whole way? And how much fuel did it require to get from Hiroshima to my street (a distance of, I don't know, about 150 miles.) It's obvious which choice is better for the environment. I'm not sure why everyone isn't complaining about this, since we sure do enough complaining when it comes to filling up our gas tanks. And we're paying for it- if you're not paying for it at the cash register, you're paying when you pay your taxes, since farms (of any size, I believe) can deduct their transportation expenses. The average item on your grocery store shelf probably traveled farther than you did on your summer vacation this year, according to Animal, Vegetable, Miracle.

The other amazing thing to me is that these lemons cost EXACTLY the same amount, despite the wide difference in cost in getting to my local MaxValu. So which farmer will be getting more of my money? Guess. Which lemon did I buy? That's right.

Being in Japan has made me more aware of things like seasonality and local crops. While the Japanese, like Americans, enjoy the luxury of having everything, all the time, for the most part foods are enjoyed only when they're in season. I have recipe cards that tell me what season I should cook each dish in. At first I thought it was silly, I had a mentality of "I can eat onion soup whenever I want!" and so on. But it makes sense, considering our living situation. In February, no Japanese person would say "Oh, I just want something light tonight, like a salad" and then complain about being cold and turn up the heat to 80 degrees. Because you can't. It is 40 degrees indoors, there is no central heat, and if you don't plan on freezing while you sleep, you had better eat some stew for dinner. I'm not saying it's perfect. If I had the choice, I'd go for the central heat, without a doubt. But I'd make sure to eat lots of stew and take lots of baths in the winter, to save some money and help the environment too.

The Japanese also firmly believe in local specialties, another concept I thought was dumb at first. Just about every city has something they are famous for. A city near me, Akashi, is famous for its particular style of grilled octopus balls (they dip them in broth) and there are countless different types of noodles. Every bag of rice is clearly labeled with its area of origin. People travel to Hokkaido just to try the fresh crabs. To me, it seemed silly, because couldn't anyone make some broth for their octopus balls? Well, they could, but Akasahi is on the Japanese Inland Sea, and they probably use some sort of local seaweed that tastes different from the seaweed that grows near Okinawa or Tokyo. It's widely accepted that wines grown in different regions or even different counties will taste different. Why not food? When I ate crab in Hokkaido this summer, it tasted fresher than any other crab I've had here. There's no substitute for it. When I returned from Hokkaido, my coworker asked me these questions, in order:

Her: Welcome back! Did you have a good trip?

Me: Yes, it was very relaxing.

Her: Did you eat jingus kan? (grilled mutton on sticks, a famous Sapporo dish)

Me: No, but I ate a lot of ramen. (Sapporo is also famous for its style of ramen.)

Her: How about crab?

And so on. And don't forget the number one most important thing of Japanese vacations-- you must bring back o-miyage, or souvenirs. This is ALWAYS food. The idea is that you should bring back some local food for all your coworkers to sample. From various vacations, I have brought back chocolates, chips made out of bitter gourds, fruit-flavored cookies, tofu cookies, bean-filled dumplings, buckwheat pancakes, and so on.

I think that if Barbara Kingsolver were to come to Japan, she would be disappointed that Japanese mothers do not "take the time to roll out the sushi by hand," as she suggests in her book. The only people I know who make sushi are sushi chefs, and no, even in Japan, there is no such thing as a "sushi machine." But she would be pleased to find a- dare I say it?- UNIQUE food culture that is built entirely upon eating local food, in season.

Thursday, July 31, 2008

Japan: Year One

On Tuesday of next week, it will have been one year since I first set foot in the Land of the Rising Sun. I wanted to take this opportunity to reflect a little bit on the experience and how it's changed me and the way I see the world, in part to convince myself that I'm not wasting my time here.

The most obvious thing that comes to mind is that I'm better on a bike now than at any other point in my life. Even when I was really young, like 10 years old, and the bike was my primary means of transportation, I couldn't do all the cool things my friends could do, like ride with no hands. Now, I'm proud to say that not only can I ride a bike with no hands, but also while holding an umbrella, texting on a cell phone, and avoiding old ladies who don't bother to look when they step out onto the sidewalk directly into my path.

The second is that while I'm by no means proud of my Japanese, I speak considerably more than I did when I came. And I can understand far more than I can speak, as I'm sure is often the case. My main regret is that I didn't start seriously studying the language sooner, so I wasted a lot of time trying to absorb Japanese through osmosis when I could have been going to my Kumon/conversation lessons every week from Day 1. Unfortunately, Japanese isn't quite like Spanish or Italian, which people living in those countries tend to "pick up" after spending a certain amount of time there, and it takes considerably more time to become proficient if you don't start hitting the books right away. Indeed, the only foreigners I know who have excellent Japanese either 1.) studied it previously in college, or 2.) have simply lived here for a long, long time. Since neither is true in my case, I should have been more serious about learning the language from the beginning. But hindsight is always 20/20, as they say, and I'll just have to work doubly hard from now on to catch up.

The third thing is that I'm much more aware of the seasons. This mostly has to do with the fact that you're exposed to the weather to a greater extent than back home. The lack of insulation or central air and heating means that you're hotter in the summer and colder in the winter, which of course is the natural order of things. This stands in direct contrast to America, where we frequently turn up the a/c so much during the summer that we have to put on jackets while indoors. Also, certain fruits and vegetables, as well as certain items on restaurant menus, are only available during specific times of the year. Now I know, for example, when eggplants are cheapest, when not to buy grapes, and when nabe will be widely available at restaurants.

Fourth is that Katie and I have made quite a few friends in a year, both foreign and Japanese. We didn't really start hanging out with the local kids in earnest until this spring, so we missed out on a lot of good times. Now she and I are more socially involved and we frequently find ourselves booked solid the entire weekend (and often during the week when we have no previous plans). This has been the most welcome change from how we spent the majority of our time at the beginning of the year.

Fifth is that I've managed to do quite a bit of traveling in the last year. Domestically, I visited many places and got to see quite a bit of the western part of Japan. I was also able to visit Korea, Malaysia, and Singapore: three places I never thought I'd ever be able to visit, but which living in Japan has made accessible and convenient. This summer Katie and I are going to Hokkaido with her family as well as to Vietnam, so opportunities to get out and see the world continue to appear, though with gas prices being what they are, such opportunities are getting pricier. Hopefully it won't prove too detrimental to our insatiable wanderlust and we'll be just as active in the coming year as we were in the past one.

Sixth is that I've been able to save a substantial amount of money. With little in the way of expenses, and with no debt between us, both she and I are making the most of our situation. I need to become more financially savvy, as right now most of my money's sitting in a Japanese bank accruing very little in the way of interest. That will be one of my goals for the coming year.

Seventh is how I've changed physically. I'm now a morning person, and I can't seem to sleep past 8 AM anymore even if I try. Katie and I often cook for ourselves using fresh ingredients, so we tend to eat well. We also go for a morning run three times a week, which combined with my twice-daily 40 minute commute by bike, has served to whip me into half-decent shape (though the daily biking has given me quite the embarrassing farmer's tan). The other weekend I found myself spending Saturday climbing up approximately 1400 steps - the equivalent of a 70 storey building - to visit a shrine, only to spend the next two days cycling 75 kilometers across an island chain in the Inland Sea. A year ago, if you told me I'd do something like that, I'd ask you what you were smoking, and if you could bear to part with any. There's so much to do in Japan in the way of outdoor activities - hiking, skiing, etc. - that you're really doing yourself a disservice if you stay cooped up all the time.

There are plenty more to mention, but since seven's a nice number, I'll stop there. I'm definitely looking forward to seeing what this next year in Japan has in store. Whatever happens, it certainly won't be boring.

-Bob

The most obvious thing that comes to mind is that I'm better on a bike now than at any other point in my life. Even when I was really young, like 10 years old, and the bike was my primary means of transportation, I couldn't do all the cool things my friends could do, like ride with no hands. Now, I'm proud to say that not only can I ride a bike with no hands, but also while holding an umbrella, texting on a cell phone, and avoiding old ladies who don't bother to look when they step out onto the sidewalk directly into my path.

The second is that while I'm by no means proud of my Japanese, I speak considerably more than I did when I came. And I can understand far more than I can speak, as I'm sure is often the case. My main regret is that I didn't start seriously studying the language sooner, so I wasted a lot of time trying to absorb Japanese through osmosis when I could have been going to my Kumon/conversation lessons every week from Day 1. Unfortunately, Japanese isn't quite like Spanish or Italian, which people living in those countries tend to "pick up" after spending a certain amount of time there, and it takes considerably more time to become proficient if you don't start hitting the books right away. Indeed, the only foreigners I know who have excellent Japanese either 1.) studied it previously in college, or 2.) have simply lived here for a long, long time. Since neither is true in my case, I should have been more serious about learning the language from the beginning. But hindsight is always 20/20, as they say, and I'll just have to work doubly hard from now on to catch up.

The third thing is that I'm much more aware of the seasons. This mostly has to do with the fact that you're exposed to the weather to a greater extent than back home. The lack of insulation or central air and heating means that you're hotter in the summer and colder in the winter, which of course is the natural order of things. This stands in direct contrast to America, where we frequently turn up the a/c so much during the summer that we have to put on jackets while indoors. Also, certain fruits and vegetables, as well as certain items on restaurant menus, are only available during specific times of the year. Now I know, for example, when eggplants are cheapest, when not to buy grapes, and when nabe will be widely available at restaurants.

Fourth is that Katie and I have made quite a few friends in a year, both foreign and Japanese. We didn't really start hanging out with the local kids in earnest until this spring, so we missed out on a lot of good times. Now she and I are more socially involved and we frequently find ourselves booked solid the entire weekend (and often during the week when we have no previous plans). This has been the most welcome change from how we spent the majority of our time at the beginning of the year.

Fifth is that I've managed to do quite a bit of traveling in the last year. Domestically, I visited many places and got to see quite a bit of the western part of Japan. I was also able to visit Korea, Malaysia, and Singapore: three places I never thought I'd ever be able to visit, but which living in Japan has made accessible and convenient. This summer Katie and I are going to Hokkaido with her family as well as to Vietnam, so opportunities to get out and see the world continue to appear, though with gas prices being what they are, such opportunities are getting pricier. Hopefully it won't prove too detrimental to our insatiable wanderlust and we'll be just as active in the coming year as we were in the past one.

Sixth is that I've been able to save a substantial amount of money. With little in the way of expenses, and with no debt between us, both she and I are making the most of our situation. I need to become more financially savvy, as right now most of my money's sitting in a Japanese bank accruing very little in the way of interest. That will be one of my goals for the coming year.

Seventh is how I've changed physically. I'm now a morning person, and I can't seem to sleep past 8 AM anymore even if I try. Katie and I often cook for ourselves using fresh ingredients, so we tend to eat well. We also go for a morning run three times a week, which combined with my twice-daily 40 minute commute by bike, has served to whip me into half-decent shape (though the daily biking has given me quite the embarrassing farmer's tan). The other weekend I found myself spending Saturday climbing up approximately 1400 steps - the equivalent of a 70 storey building - to visit a shrine, only to spend the next two days cycling 75 kilometers across an island chain in the Inland Sea. A year ago, if you told me I'd do something like that, I'd ask you what you were smoking, and if you could bear to part with any. There's so much to do in Japan in the way of outdoor activities - hiking, skiing, etc. - that you're really doing yourself a disservice if you stay cooped up all the time.

There are plenty more to mention, but since seven's a nice number, I'll stop there. I'm definitely looking forward to seeing what this next year in Japan has in store. Whatever happens, it certainly won't be boring.

-Bob

Sunday, July 20, 2008

Moderation

Some Japanese people react very strangely to summertime. There are two major types of people (and I see them on a daily basis):

The first type is the ganguro girls, who look somewhat like a stereotypical California girl. They are not American. They are Japanese. Somehow they have convinced themselves if they grow their hair very long and then bleach, and perm and tease it, it will look like they have naturally curly blond hair. Actually, when you perm and bleach fine, straight black hair, it turns out an orange mess. They also tan excessively so their skin kind of matches their hair. They wear shorts that are about the length from my outstretched thumb to my pointer finger. Their shoes are about that same height. The strangest part is that they put white eyeliner all around their eyes and sometimes down the middle of their nose. In the summer they like to hang out at the beach, wearing bikinis with lots of extra padding on the chest, where they can get their photo taken by creepy middle aged men who walk around the beach with giant cameras and photograph any mildly attractive girl.

The second I like to call the beekeepers. These are women, usually aged 30 and above, who are petrified of getting a suntan. Most women in East Asia dislike suntans because it looks like they've been out working in the sun or something else low-class. Elbow length gloves or long sleeves are de rigeur, even when it's 100 degrees out. The grandmas are the most extreme. When I go jogging at 6:30 am, I often see lots of older people out exercising. The women wear long sleeves or long gloves with their short sleeves, and a hat. The really hardcore ones wear long pants and long sleeves, with gloves, of course. They put a towel on their heads (covers the back of the neck) and put a hat (very long brim, naturally) on top of that. Then they pull the ends of the towel around to the front of their face and clip it with a clothespin. Now it's time to go for a walk! At 6:30 am there is no way there is enough UV to change your skin color. They literally look like they were taking care of their bees, and then suddenly decided to go exercise. That's how much skin is exposed. I think perhaps the Taliban was more lenient, I think during their regime you could at least show your hands as well as your eyes.

I'm not sure who scares me more.

The first type is the ganguro girls, who look somewhat like a stereotypical California girl. They are not American. They are Japanese. Somehow they have convinced themselves if they grow their hair very long and then bleach, and perm and tease it, it will look like they have naturally curly blond hair. Actually, when you perm and bleach fine, straight black hair, it turns out an orange mess. They also tan excessively so their skin kind of matches their hair. They wear shorts that are about the length from my outstretched thumb to my pointer finger. Their shoes are about that same height. The strangest part is that they put white eyeliner all around their eyes and sometimes down the middle of their nose. In the summer they like to hang out at the beach, wearing bikinis with lots of extra padding on the chest, where they can get their photo taken by creepy middle aged men who walk around the beach with giant cameras and photograph any mildly attractive girl.

The second I like to call the beekeepers. These are women, usually aged 30 and above, who are petrified of getting a suntan. Most women in East Asia dislike suntans because it looks like they've been out working in the sun or something else low-class. Elbow length gloves or long sleeves are de rigeur, even when it's 100 degrees out. The grandmas are the most extreme. When I go jogging at 6:30 am, I often see lots of older people out exercising. The women wear long sleeves or long gloves with their short sleeves, and a hat. The really hardcore ones wear long pants and long sleeves, with gloves, of course. They put a towel on their heads (covers the back of the neck) and put a hat (very long brim, naturally) on top of that. Then they pull the ends of the towel around to the front of their face and clip it with a clothespin. Now it's time to go for a walk! At 6:30 am there is no way there is enough UV to change your skin color. They literally look like they were taking care of their bees, and then suddenly decided to go exercise. That's how much skin is exposed. I think perhaps the Taliban was more lenient, I think during their regime you could at least show your hands as well as your eyes.

I'm not sure who scares me more.

Monday, June 16, 2008

Through fresh eyes

After you've been living in a place for a while, you tend to forget the things that shocked or amused you so much when you first arrived. You take for granted the fact that, in Japan anyway, there are cigarette vending machines on every corner. You understand that you don't have to tip at restaurants, and the displayed price for the convenience store candy bar is exactly what you pay at the register - you don't give it a second thought. You think nothing of the teenage kid decked out in his punk-rock finest, hair dyed red, a skull-n-crossbones patch safety pinned to his black bowler hat, strolling arm in arm with a girl in full kimono, a Louis Vuitton clutch dangling at her side. So nothing amuses me more than going to all my favorite locations accompanied by people who are seeing Japan for the first time in their lives through fresh eyes, wide and bright from the adrenaline rush that comes from actually being in a place to which you never thought you'd have the opportunity to travel.

So it was that Katie and I were called upon by our Japanese surrogate parents, the Masaokas (to whom we are indebted forever for all the help they've given us over the past year, not the least of which involved guiding us through the labyrinthine entrails of Japanese hospitals and American insurance companies when Katie had her emergency appendectomy last August), to come to Kyoto Station to meet our predecessors - the people who had my same job and lived in my very house two years ago. We knew precious little about Ned and Megan: they were from Washington State and had translated the menu at the Chinese restaurant next door which we frequent into English. That's about it. So we were excited to meet them and, selfishly, were excited to have any excuse at all to go to Kyoto.

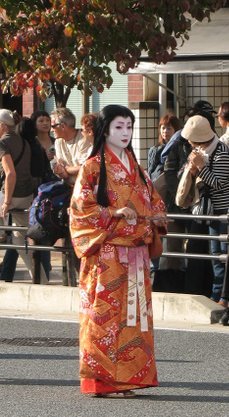

When we got to Kyoto Station (Ned refers to it as the Death Star because it is the largest and most futuristic-looking building you'll ever set foot in), we saw Mr. and Mrs. Masaoka surrounded by a group of foreign kids; they looked like high school students. "Oh no," Katie said, "Mrs. Masaoka found a group of high school kids on a school trip and has probably taken it upon herself to personally show them around for the day." Such behavior would be totally normal for Mrs. Masaoka, which goes to show you the kind of person she is. She was dressed in summer kimono, which we suspect she does for the benefit of the foreigners she meets (when Katie's family came in March she showed up to our house dressed like that, for example). As it turned out though, Megan and Ned are both teachers back in Spokane and Ned had brought along some of the students from his Japanese class - apparently he teaches mainly social studies but also beginning Japanese on the side. So Katie and I go down to meet 12 more people than we had originally expected to, and we didn't quite know what to make of the situation. As it turned out, the kids were all really nice and subdued from the jet lag, so we were mercifully spared the horrific fate of keeping tabs on a bunch of teenagers running amok around the Old Capital.

Ned and Megan were incredibly nice people and a lot of fun to talk to; they knew the area around our house quite well as they had lived there, of course, so we talked about that quite a bit. Ned's students seemed to be quite mature and responsible as it turned out, so Katie and I were able to talk to them and answer their questions about living in Japan. The best part, of course, was just watching their reactions to things we simply take for granted living here: the ubiquitous vending machines, the lack of public trash cans, the fashion, just to name a few. To watch them taking pictures of the most mundane objects and shouting excitedly about stuff you see on your way to work every day energizes you and makes you feel privileged to live here. I often felt the same way when I was working downtown in DC and would walk down Pennsylvania Avenue on my lunch break past the White House, passing groups of tourists pointing and taking pictures. I was so fortunate, I thought, to live in such a place. I've no doubt my friends currently scattered across the globe experience the same when they spy a group of out-of-towners talking excitedly to each other, bedecked in backpacks and walking shoes, cameras at the ready, able to see things they'd long since forgotten through fresh eyes.

So it was that Katie and I were called upon by our Japanese surrogate parents, the Masaokas (to whom we are indebted forever for all the help they've given us over the past year, not the least of which involved guiding us through the labyrinthine entrails of Japanese hospitals and American insurance companies when Katie had her emergency appendectomy last August), to come to Kyoto Station to meet our predecessors - the people who had my same job and lived in my very house two years ago. We knew precious little about Ned and Megan: they were from Washington State and had translated the menu at the Chinese restaurant next door which we frequent into English. That's about it. So we were excited to meet them and, selfishly, were excited to have any excuse at all to go to Kyoto.

When we got to Kyoto Station (Ned refers to it as the Death Star because it is the largest and most futuristic-looking building you'll ever set foot in), we saw Mr. and Mrs. Masaoka surrounded by a group of foreign kids; they looked like high school students. "Oh no," Katie said, "Mrs. Masaoka found a group of high school kids on a school trip and has probably taken it upon herself to personally show them around for the day." Such behavior would be totally normal for Mrs. Masaoka, which goes to show you the kind of person she is. She was dressed in summer kimono, which we suspect she does for the benefit of the foreigners she meets (when Katie's family came in March she showed up to our house dressed like that, for example). As it turned out though, Megan and Ned are both teachers back in Spokane and Ned had brought along some of the students from his Japanese class - apparently he teaches mainly social studies but also beginning Japanese on the side. So Katie and I go down to meet 12 more people than we had originally expected to, and we didn't quite know what to make of the situation. As it turned out, the kids were all really nice and subdued from the jet lag, so we were mercifully spared the horrific fate of keeping tabs on a bunch of teenagers running amok around the Old Capital.

Ned and Megan were incredibly nice people and a lot of fun to talk to; they knew the area around our house quite well as they had lived there, of course, so we talked about that quite a bit. Ned's students seemed to be quite mature and responsible as it turned out, so Katie and I were able to talk to them and answer their questions about living in Japan. The best part, of course, was just watching their reactions to things we simply take for granted living here: the ubiquitous vending machines, the lack of public trash cans, the fashion, just to name a few. To watch them taking pictures of the most mundane objects and shouting excitedly about stuff you see on your way to work every day energizes you and makes you feel privileged to live here. I often felt the same way when I was working downtown in DC and would walk down Pennsylvania Avenue on my lunch break past the White House, passing groups of tourists pointing and taking pictures. I was so fortunate, I thought, to live in such a place. I've no doubt my friends currently scattered across the globe experience the same when they spy a group of out-of-towners talking excitedly to each other, bedecked in backpacks and walking shoes, cameras at the ready, able to see things they'd long since forgotten through fresh eyes.

Monday, June 9, 2008

Update 6/9

Well, yet another week begins, with Monday and Tuesday leaving me very little to do aside from my Japanese lessons. This past weekend was a lot of fun: on Saturday we had some of our new Japanese friends over for Korean food. One of them brought her 5 year-old daughter who's enrolled at a local international school and thus speaks English relatively well. We taught her how to play Life (the board game), the Japanese version of which Katie found at the local recycle shop for a measly 300 yen. For dinner we made sam gyeop sal, or barbecued pork grilled alongside various toppings which you then roll into a sesame leaf and eat with your hands. It tasted exactly the same as what we ate in Busan, which pleased us - and our tummies - greatly.

Sunday I really wanted to get out of the house, having spent Saturday cleaning up, going grocery shopping, and helping to prepare dinner. Katie and I decided to go to the Osaka aquarium, which we had heard was a great way to spend an afternoon. After the obligatory Sunday breakfast of blueberry pancakes (the packet of frozen blueberries we bought at Costco several months ago are still going strong), Katie tended the garden for a bit, then we headed downtown. Admission to the aquarium was outrageously expensive, so we decided to buy a day pass which, in addition to covering the aquarium's entrance fee, would allow us to ride the subway as much as we wanted for free. The aquarium itself looks like a giant modern art installation, sitting on Osaka Bay. Inside we saw all kinds of fish in an incredible array of sizes, shapes, and terrifying-ness. The main attraction is the whale shark which easily dwarfs the next biggest fish in the entire aquarium several times over. The best part of the whole thing, though, wasn't what lives in the water, but what spends most of its time above it. Katie and I spent a lot of time at the otter, penguin, seal, and sealion tanks. It helps that those animals are the cutest ones, but there you are.

After the aquarium we rode the subway to Shinsaibashi in South Osaka to eat at an Ethiopian restaurant we had heard about. It was expensive (and we were the only ones eating there, which worried me a little), but the food was so damn good. It made me miss Mesob in Charlottesville so much, and filled me with regret for all of the great Ethiopian restaurants in DC I neglected to try when I lived so nearby. At the bar sat two barrel-chested and bearded Ethopian fellows - I could tell they were authentically Ethiopian because of their narrow-bridged noses. Otherwise, it would be safe to assume they were Nigerian, since those are really the only black people you see in Japan on a regular basis. They spoke a bizarre pidgin of English and Japanese, and chatted away over their beers unperturbed by the conspicuous lack of customers on a Sunday evening. Sometimes Katie and I wonder how it is that these places we love - a Vietnamese hole-in-the-wall in Nishinomiya, a pizzeria in Osaka that serves up pizzas blessedly unadorned with creative Japanese topping like corn and mayonnaise, any number of Turkish restaurants in Kobe, etc. - manage to stay in business when we seem to be the only ones patronizing them. I like to think they're all fronts for the Yakuza.

After the aquarium we rode the subway to Shinsaibashi in South Osaka to eat at an Ethiopian restaurant we had heard about. It was expensive (and we were the only ones eating there, which worried me a little), but the food was so damn good. It made me miss Mesob in Charlottesville so much, and filled me with regret for all of the great Ethiopian restaurants in DC I neglected to try when I lived so nearby. At the bar sat two barrel-chested and bearded Ethopian fellows - I could tell they were authentically Ethiopian because of their narrow-bridged noses. Otherwise, it would be safe to assume they were Nigerian, since those are really the only black people you see in Japan on a regular basis. They spoke a bizarre pidgin of English and Japanese, and chatted away over their beers unperturbed by the conspicuous lack of customers on a Sunday evening. Sometimes Katie and I wonder how it is that these places we love - a Vietnamese hole-in-the-wall in Nishinomiya, a pizzeria in Osaka that serves up pizzas blessedly unadorned with creative Japanese topping like corn and mayonnaise, any number of Turkish restaurants in Kobe, etc. - manage to stay in business when we seem to be the only ones patronizing them. I like to think they're all fronts for the Yakuza.

Tuesday, May 27, 2008

Outside looking in

As you know, I try to keep up with current events as much as I can, and the fact that I have loads of free time at school means loads of time to read the news religiously. I have a few favorite websites - Drudge Report, Fark.com, CNN, BBC - but for all things Japan-related, I turn to JapanToday.com. Japan Today's journalism isn't as good as the other major English language newspaper in Japan, the Japan Times, but it does give its online readers the opportunity to comment on articles. So I mostly read the comments, truth be told.

Anyway, today I clicked on an article - well, more a poll than an article - that asked readers if they thought the word gaijin was a racist term. This particular topic is one of frequent debate among foreign residents and visitors of Japan, but for those of you unfamiliar with it, here's a little background:

Gaijin, 外人, literally means "outside person", and is commonly used to refer to foreigners. It's an abbreviation of the more "official" term gaikokujin, 外国人, or "outside country person". Most foreigners overwhelmingly prefer the latter term, because they consider the former to reinforce the idea that they, as individuals (regardless of their country of origin), are inexorably "outside" Japanese society. Which is true, but nevertheless, it takes the edge off when you refer to someone as being from a foreign country rather than label them as a foreigner.

Further, while you could translate gaijin as "foreigner", it doesn't mean the same thing to the Japanese as it means to most of us. For non-Japanese, being a foreigner usually means being in a country other than the one you come from. So while someone from France would be a foreigner in the U.S., an American would be a foreigner in France. To the Japanese, however, being a foreigner means being something other than Japanese. So, a Japanese would consider her American neighbor to be a foreigner (non-Japanese), but when she goes on vacation to Hawaii, she finds herself surrounded by "foreigners" (again, non-Japanese). It sounds funny to us to hear a Japanese person, when vacationing abroad, say, "Look at all the gaijin!". But we must remember that it's not some weird insular provincialism at work here (at least not entirely), but rather a simple difference in how Japanese and non-Japanese conceive of "the outsider".

Anyway, a lot of my fellow expats get miffed when they hear that particular term, staging a mini protest every time (it's gaikokujin, thank you very much). Others bandy it about quite liberally, in some instances ironically (hey, look at the dumb gajin over here!) and in others quite earnestly. The word definitely means different things to different people, but I personally think it has a lot to do with the context in which the word is used, and the intent of the person who uses it. Obviously an drunk densha otoko yelling, "Get out of Japan, gaijin!" means it in a racist way, but your buddy Takeshi who says, "I have a lot of gaijin friends," doesn't. It's all about context, you see. I have always believed that no object in this world has meaning other than that which we impart to it. In other words, words mean what you want them to mean. As my former boss was so fond of saying, "Perception is reality."

That quote's a pretty good end to this entry, but I feel like I could write so much more about the relationship between foreigners living in Japan and the Japanese - and indeed, dozens of books have already been written about that very subject. But for now, I'd like to leave you with a handy guide to what I call the "Hierarchy of Foreigners" which will help you locate your place in Japanese society, should you ever wind up living in or visiting this island nation behind the sun. It goes like this:

1. Japanese - all strata of Japanese society, from the Emperor on down to the burakumin, people descended from the lowest caste who face discrimination even today. As long as you have pure Japanese blood, you're in this group. Welcome to the club!

2. Japanese returnees, halfus, Ryukyuans, Ainu - maybe you're Japanese, or half-Japanese, but you've spent some time in a foreign country and have, as a consequence, picked up some weird habits. Maybe your Japanese language ability has suffered a bit. Unfortunately, when you come back to Japan, you'll be bullied accordingly until you can properly "fit in" again.

3. White people - the Japanese look up to you and look to your European heritage as a source of inspiration. They don't necessarily want you living in their neighborhoods or marrying their daughters (though most are probably OK with it these days), but they're more than happy to practice their English on you and appropriate your food and fashion.

4. Black people - you're considered cool, and many Japanese will try to emulate your music and fashion (albeit with hilarious consequences), but to many Japanese, you're incredibly scary. Be prepared to face this grim reality, though you might win some points if you casually mention that you know Beyonce (and you probably won't be the one who brings it up).

5. Chinese and Koreans - you are blessed, or cursed, with the ability to blend in - at least until someone starts talking to you and you don't understand what they're saying. The Japanese find you to be quite disturbing because they think of themselves as being special and unique, but yet you, a non-Japanese, managed to fool them into thinking that you were one of them. Also, their contempt for you has well-established historical roots, and don't be surprised if they regale you with tales of how they "liberated" your country in WWII.

6. All other Asians - same as #5, but unlike many Chinese and Koreans, you lack the ability to blend in as well as they. The historical stuff still applies, though. Good luck!

-Bob

Anyway, today I clicked on an article - well, more a poll than an article - that asked readers if they thought the word gaijin was a racist term. This particular topic is one of frequent debate among foreign residents and visitors of Japan, but for those of you unfamiliar with it, here's a little background:

Gaijin, 外人, literally means "outside person", and is commonly used to refer to foreigners. It's an abbreviation of the more "official" term gaikokujin, 外国人, or "outside country person". Most foreigners overwhelmingly prefer the latter term, because they consider the former to reinforce the idea that they, as individuals (regardless of their country of origin), are inexorably "outside" Japanese society. Which is true, but nevertheless, it takes the edge off when you refer to someone as being from a foreign country rather than label them as a foreigner.

Further, while you could translate gaijin as "foreigner", it doesn't mean the same thing to the Japanese as it means to most of us. For non-Japanese, being a foreigner usually means being in a country other than the one you come from. So while someone from France would be a foreigner in the U.S., an American would be a foreigner in France. To the Japanese, however, being a foreigner means being something other than Japanese. So, a Japanese would consider her American neighbor to be a foreigner (non-Japanese), but when she goes on vacation to Hawaii, she finds herself surrounded by "foreigners" (again, non-Japanese). It sounds funny to us to hear a Japanese person, when vacationing abroad, say, "Look at all the gaijin!". But we must remember that it's not some weird insular provincialism at work here (at least not entirely), but rather a simple difference in how Japanese and non-Japanese conceive of "the outsider".

Anyway, a lot of my fellow expats get miffed when they hear that particular term, staging a mini protest every time (it's gaikokujin, thank you very much). Others bandy it about quite liberally, in some instances ironically (hey, look at the dumb gajin over here!) and in others quite earnestly. The word definitely means different things to different people, but I personally think it has a lot to do with the context in which the word is used, and the intent of the person who uses it. Obviously an drunk densha otoko yelling, "Get out of Japan, gaijin!" means it in a racist way, but your buddy Takeshi who says, "I have a lot of gaijin friends," doesn't. It's all about context, you see. I have always believed that no object in this world has meaning other than that which we impart to it. In other words, words mean what you want them to mean. As my former boss was so fond of saying, "Perception is reality."

That quote's a pretty good end to this entry, but I feel like I could write so much more about the relationship between foreigners living in Japan and the Japanese - and indeed, dozens of books have already been written about that very subject. But for now, I'd like to leave you with a handy guide to what I call the "Hierarchy of Foreigners" which will help you locate your place in Japanese society, should you ever wind up living in or visiting this island nation behind the sun. It goes like this:

1. Japanese - all strata of Japanese society, from the Emperor on down to the burakumin, people descended from the lowest caste who face discrimination even today. As long as you have pure Japanese blood, you're in this group. Welcome to the club!

2. Japanese returnees, halfus, Ryukyuans, Ainu - maybe you're Japanese, or half-Japanese, but you've spent some time in a foreign country and have, as a consequence, picked up some weird habits. Maybe your Japanese language ability has suffered a bit. Unfortunately, when you come back to Japan, you'll be bullied accordingly until you can properly "fit in" again.

3. White people - the Japanese look up to you and look to your European heritage as a source of inspiration. They don't necessarily want you living in their neighborhoods or marrying their daughters (though most are probably OK with it these days), but they're more than happy to practice their English on you and appropriate your food and fashion.

4. Black people - you're considered cool, and many Japanese will try to emulate your music and fashion (albeit with hilarious consequences), but to many Japanese, you're incredibly scary. Be prepared to face this grim reality, though you might win some points if you casually mention that you know Beyonce (and you probably won't be the one who brings it up).

5. Chinese and Koreans - you are blessed, or cursed, with the ability to blend in - at least until someone starts talking to you and you don't understand what they're saying. The Japanese find you to be quite disturbing because they think of themselves as being special and unique, but yet you, a non-Japanese, managed to fool them into thinking that you were one of them. Also, their contempt for you has well-established historical roots, and don't be surprised if they regale you with tales of how they "liberated" your country in WWII.

6. All other Asians - same as #5, but unlike many Chinese and Koreans, you lack the ability to blend in as well as they. The historical stuff still applies, though. Good luck!

-Bob

Thursday, May 22, 2008

It's easy being green

Apologies for all the posts this week; consider it my way of making up for the lengthy waiting times between some of our past posts. It's exam week at school (and in Japan, it seems like every other week is exam week) which means I have zilch to do all day. I don't bring this up to Katie, of course, whose admittedly understandable response would be to glare menacingly into my very soul, given that her school has recently put her in charge of potty training someone else's kids all day long. We'll keep you posted on how that goes.

In the meantime, I have some downtime with which to wax literary about a variety of topics. So today, I want to talk about composting. More specifically, I want to encourage you all to try it.

Now while my political leanings are fairly left of center, I don't consider myself the leftist type. I certainly wouldn't call myself a hippie tree-hugger, for instance. But recently, and maybe it has something to do with living in a country where so little is wasted, I've found myself becoming more and more interested in conservation and the little things normal folks like you and me can do to reduce the amount of waste in our lives.

In Japan, you don't have a choice when it comes to recycling - it's mandatory. It varies from location to location, but here in Amagasaki, you have to separate your burnable trash (food wrappers and various kitchen waste) from your non-burnable trash (plastic and glass bottles and cans). Each is picked up on a different day of the week. Further, there are one or two days a month where the trash guys come around and pick up things like paper & cardboard, metal objects, and even old appliances, though sometimes you have to pay extra for the latter if it's a large item like a TV or old refrigerator. So getting people to recycle in Japan is not an issue; they're doing it all the time.

The Japanese don't really complain about the whole "mandatory" part, because they have a seemingly built-in contempt for wastefulness. They even have an expression they like to trot out fairly often: mottainai, or "what a waste." Given the limited amount of livable space in the country, it's no surprise that everyone's keenly aware that there simply aren't landfills where garbage "magically" disappears to every week. Contrast this with the US, where New York City and New Jersey actually send their garbage to Virginia because they can't deal with it all. I can't imagine Hyogo Prefecture, for instance, knocking on, say, Niigata's door and asking, however politely (it is Japan, after all), that shitsureishimasu, very sorry, but could it humbly dispose of its humble garbage in Niigata's honorable backyard? There's just no space that hasn't already been claimed by people, industry & commerce, or agriculture.

Now there are a lot of behaviors Western journalists, upon returning home from their week or two in Japan, claim we should adopt from the frugal and efficient Japanese. Most of them are complete nonsense, and anyone who's spent more than a month in the country will tell you the same. However, I do think we should follow Japan's example regarding our attitudes and behaviors towards waste. It's with this in mind that Katie and I decided to start a compost pile.

First, what is compost? They sell it at any home supply store: it's that stuff you add to your soil to make your plants happy and healthy. That's the long and short of it. But what is it, really? Compost is the result of millions of chemical reactions occurring simultaneously, breaking down organic matter into its simplest components - carbon and nitrogen - the appropriate combination of which is like black gold when it comes time to grow those tomatoes out back. If it helps, think of the process as "controlled rotting".

Second, why should you compost? About 1/3 of your kitchen waste doesn't need to go in the trash can. You throw away things like banana peels, apple cores, autumn leaves, and grass clippings without a second thought, then trash day comes and the nice people take your bags to the local landfill, where that perfectly useful organic garbage is mixed in with plastics, metals, chemicals, and other unsavory and un-biodegradable refuse, buried, and as a result takes far, far longer to break down than it would have if properly composted. Also, you'll have a nice pile of compost you can use on your flowers and plants, and it won't cost you a cent. What's more, if you have enough, you can share it with your more horticulturally-inclined friends and neighbors (and charge them a nominal fee).

Third, how easy is it to make a compost pile? Easy! If I, a lazy individual by almost every objective standard, can make one, then so can you. I'll give you an example of how easy it is: did you just eat a banana for breakfast? Are you holding the peel in your hand, ready to drop it into the rubbish bin? Why don't you, instead, take that peel out to the yard, and just drop it. That's right, just drop it right on the ground. There you go. That's the beginning. It's that easy. After that, just keep adding more and more organic material to the pile. Here are some links to help you get started:

You may run into some hitches here and there, but in general, a well-maintained pile stocked with appropriate material will not stink and will not attract rodents or other pests. Even if you experience problems, they're usually fixable. For example, right now our pile has a lot of ants and fruit flies (solution: bury exposed fruit and veggies lower in the pile and mix pile more often to disturb ant colonies) and smells strongly of ammonia (solution: too much "green" material, need to add more "brown"). Check out the troubleshooting sections of the above websites to guide you through any issues you may encounter.

Just remember, mottainai, and spare the trash man a hernia.

Good luck, and happy composting!

-Bob

In the meantime, I have some downtime with which to wax literary about a variety of topics. So today, I want to talk about composting. More specifically, I want to encourage you all to try it.

Now while my political leanings are fairly left of center, I don't consider myself the leftist type. I certainly wouldn't call myself a hippie tree-hugger, for instance. But recently, and maybe it has something to do with living in a country where so little is wasted, I've found myself becoming more and more interested in conservation and the little things normal folks like you and me can do to reduce the amount of waste in our lives.

In Japan, you don't have a choice when it comes to recycling - it's mandatory. It varies from location to location, but here in Amagasaki, you have to separate your burnable trash (food wrappers and various kitchen waste) from your non-burnable trash (plastic and glass bottles and cans). Each is picked up on a different day of the week. Further, there are one or two days a month where the trash guys come around and pick up things like paper & cardboard, metal objects, and even old appliances, though sometimes you have to pay extra for the latter if it's a large item like a TV or old refrigerator. So getting people to recycle in Japan is not an issue; they're doing it all the time.

The Japanese don't really complain about the whole "mandatory" part, because they have a seemingly built-in contempt for wastefulness. They even have an expression they like to trot out fairly often: mottainai, or "what a waste." Given the limited amount of livable space in the country, it's no surprise that everyone's keenly aware that there simply aren't landfills where garbage "magically" disappears to every week. Contrast this with the US, where New York City and New Jersey actually send their garbage to Virginia because they can't deal with it all. I can't imagine Hyogo Prefecture, for instance, knocking on, say, Niigata's door and asking, however politely (it is Japan, after all), that shitsureishimasu, very sorry, but could it humbly dispose of its humble garbage in Niigata's honorable backyard? There's just no space that hasn't already been claimed by people, industry & commerce, or agriculture.

Now there are a lot of behaviors Western journalists, upon returning home from their week or two in Japan, claim we should adopt from the frugal and efficient Japanese. Most of them are complete nonsense, and anyone who's spent more than a month in the country will tell you the same. However, I do think we should follow Japan's example regarding our attitudes and behaviors towards waste. It's with this in mind that Katie and I decided to start a compost pile.

First, what is compost? They sell it at any home supply store: it's that stuff you add to your soil to make your plants happy and healthy. That's the long and short of it. But what is it, really? Compost is the result of millions of chemical reactions occurring simultaneously, breaking down organic matter into its simplest components - carbon and nitrogen - the appropriate combination of which is like black gold when it comes time to grow those tomatoes out back. If it helps, think of the process as "controlled rotting".

Second, why should you compost? About 1/3 of your kitchen waste doesn't need to go in the trash can. You throw away things like banana peels, apple cores, autumn leaves, and grass clippings without a second thought, then trash day comes and the nice people take your bags to the local landfill, where that perfectly useful organic garbage is mixed in with plastics, metals, chemicals, and other unsavory and un-biodegradable refuse, buried, and as a result takes far, far longer to break down than it would have if properly composted. Also, you'll have a nice pile of compost you can use on your flowers and plants, and it won't cost you a cent. What's more, if you have enough, you can share it with your more horticulturally-inclined friends and neighbors (and charge them a nominal fee).

Third, how easy is it to make a compost pile? Easy! If I, a lazy individual by almost every objective standard, can make one, then so can you. I'll give you an example of how easy it is: did you just eat a banana for breakfast? Are you holding the peel in your hand, ready to drop it into the rubbish bin? Why don't you, instead, take that peel out to the yard, and just drop it. That's right, just drop it right on the ground. There you go. That's the beginning. It's that easy. After that, just keep adding more and more organic material to the pile. Here are some links to help you get started:

You may run into some hitches here and there, but in general, a well-maintained pile stocked with appropriate material will not stink and will not attract rodents or other pests. Even if you experience problems, they're usually fixable. For example, right now our pile has a lot of ants and fruit flies (solution: bury exposed fruit and veggies lower in the pile and mix pile more often to disturb ant colonies) and smells strongly of ammonia (solution: too much "green" material, need to add more "brown"). Check out the troubleshooting sections of the above websites to guide you through any issues you may encounter.

Just remember, mottainai, and spare the trash man a hernia.

Good luck, and happy composting!

-Bob

Wednesday, May 21, 2008

TeamKB Does Korea

Katie wrote up a summary of our recent trip to Korea and sent it to her family and friends, but since my family - whom I assume are the principal readers of this blog - have not yet seen it, I decided I'd post it here so they could read it, too.

Hello my dear readers,

As this monthly newsletter goes to press you'll notice that I am not reporting from Japan, but somewhere totally, completely different: Korea.

Day 0: We left our house at 9 pm to get a 10 pm night bus from Osaka to Fukuoka. The trip was mostly uneventful, other than the fact that the driver would stop every 2 hours, turn on all the lights, and make an announcement over the PA system that began with "I'm so sorry to wake you, but..." If he was really so sorry why didn't he just KEEP THE LIGHTS OFF!

Day 1: We arrived in Fukuoka at 6:40 am, and after eating some breakfast, we went over to the international ferry terminal. There are overnight ferries or high-speed hydrofoils (which take only 3 hours) to Busan, Korea. We opted for the hydrofoil, which was a very pleasant journey, so pleasant I slept through it. My friend Adam teaches English in Busan, so we were staying with him while we were in Korea. He and his girlfriend took us around the downtown area of Busan where we discovered such Korean fads as "face rollers" (a tool you roll on your jaw to make your face smaller) and "couples t-shirts" (2 t-shirts with matching or complementary designs, worn by young couples.) Photos of face rollers here and couples shirts here

Days 2 and 3: Sightseeing in Busan, which is on the southeastern coast of South Korea. Here are some more facts you might not know about Busan:

- It is the world's third largest port, and Asia's largest container port.

- It has thrown its hat into the ring to host the 2020 Summer Olympics (it hosted both the Asian Games and some of the World Cup in 2002.)

- Ground has been broken on the Lotte World II Tower in downtown Busan, which will be taller than any other existing skyscraper in the world. I think the Burj Dubai will be finished first though.

Days 4 and 5: We took a quick trip up to Seoul, to do some sightseeing and of course, visit North Korea. On the morning of Day 5 we took a tour of the DMZ, led by the USO. We stepped inside the building where negotiations are held-- since this building straddles the border, everyone sits on their respective sides of the table. Tourists are allowed to step across the line, so I have now legally set foot in North Korea. It... felt a lot like South Korea. The rest of the tour was fascinating, especially meeting the Army guy who led the tour. He'd only been at Camp Bonifas (nickname "In Front of Them All") for 3 weeks, yet he was already trying to extend his stay for 2 years instead of one. I guess it's better than Iraq. North Korea's government is pretty scary, but honestly I don't think they're that dangerous-- I think that it's all political, and they want the world to pay attention to them. They really couldn't try anything without having the ire of almost the entire world come down on them. Even China is trying to distance itself from North Korea. An interesting note: South and North Korea have technically not made peace, so the Korean War is not yet over.

Day 6: Having returned late the last night from Seoul, we did the only rational thing: we got up early the next day! We had to see Gyeonju, a city that is often called Korea's Kyoto for its history as the capital of the Shilla Kingdom (from about 0- 1000 AD) and abundance of cultural sights. It was a bit of a tourist circus, but worth a visit as the city is basically a giant repository of historical artifacts. We saw some giant tombs that were nearly 2000 years old, and visited a mountainside temple. We also happened to be visiting an astronomy tower at the same time a field trip of Korean 3-year-olds was there. I rescued one kid when he attempted to climb over the fence while his teachers weren't looking. I just can't get away from kids, even on vacation.Day 7: The weekend! Adam and his girlfriend Hyun-mi were off work, so we all went downtown to see a parade. We just caught the end of it-- actually it was a Korea-Japan friendship parade, which I found interesting since there tends to be a lot of distrust on the part of the Koreans towards the Japanese. Many Koreans are still angry over the colonization of the Korean peninsula, the Japanese enslaving the Korean people and raping their women, and the fact that they've never gotten so much as an apology. The parade was fun, but I didn't really catch the Korea-Japan friendship aspect. Some of the ladies in the parade saw us foreigners, and invited us to come dance-- actually I think they wanted Bob to come dance, but he was too shy so I went instead. One old man told me I was great at it, I didn't really believe him... as always, you can check Bob's Picasa account to see photos (they'll be up in a few days.) In the evening we all went to Haeundae beach, which is a great nighttime hangout since you can drink and set fireworks off on the beach. Adam's friend from Seoul met up with us there, and I found out she went to TJ and graduated in '03. Small world...Day 8: Hyun-mi's friend Jiu, who has a car, drove us out to the eastern edges of Busan, into Gijiang county, to visit a cliffside temple overlooking the sea. Adam said quite accurately that this was a day of waiting. We waited in traffic for a long time-- but the temple was totally worth it. We also waited a very long time for our meal, but it was worth it as it was very delicious, consisting entirely of Korean side dishes. I didn't know much about Korean food before I went, but I feel like I learned a lot. The side dishes were my favorite part. Every meal is served with a variety of side dishes, usually a half dozen different dishes. Kim chi is always included but the rest vary-- I couldn't even describe them to you, there is such a range. Just know that there is usually a lot of garlic and hot pepper involved. Delicious!Day 9: We left very early to catch our hydrofoil back to Japan, spent some time in Fukuoka doing some sightseeing, and, just before we caught the bus back to Osaka, we were serenaded by a homeless man outside the station who kept telling us that we were wonderful and I should have kids. Other than that, our day was pretty uneventful.

Ok, so I lied. Korea and Japan are actually pretty similar, as much as each country doesn't want to admit it. I'm still not sure exactly why. I guess that would mean facing the fact that historically, Korea and Japan both drew so much from China, from language to religion to food. The cultural similarity is still apparent-- in fact, I was able to read some signs and understand a handful of Korean words because of its similarity to Japanese through Chinese. But in the last few hundred years and especially in the present day, each country has gone its own way, so to speak, to try to differentiate itself and to make their place in the world. Each country has a lot to offer and should be proud to be compared to the other one.

Love, Katie

Tuesday, May 20, 2008

Our yard

As you know, Katie and I have been periodically getting out into the backyard, trying to make it look presentable so we can eventually throw fabulous garden parties this summer. So far, it hasn't proved to be the easiest of tasks, given that we have no easy way to mow the grass. I don't think I've ever seen or heard a lawnmower or weedeater in Japan. We resorted to using hedge clippers and small scythes to trim the grass as best we could, but of course we were left with an uneven mess - but no matter; it's not really important that it look perfect, just that it be short enough that it's not an attractive hiding place for snakes or other such unsavory creatures. So we were out there for a few hours on Sunday afternoon, whacking, cutting, clipping the brambles, and throwing half of the refuse into our compost pile and half into the drainage ditch behind the house - there's really nothing else we can do, really. It was hard work, but as it was a nice day - not too hot - it wasn't bad being outside, although I did discover that mosquitoes find me particularly delicious, despite the insect repellent I had slathered on myself.

So I get to school on Monday, at which time I'm informed that the school will be sending someone to our house on Thursday to cut our grass (the Hyogo Prefectural Board of Education owns the property and is responsible for maintaining it, although Katie and I always try to fix small problems ourselves). What luck! Just after we (mostly) finished doing that very thing ourselves, as best we could at least, given the tools we had to do the job. So now we get a professional - hurray! I can only wonder, though; is this just a coincidence? Why would the school pick this week to do some lawn maintenance, immediately after we tried doing the same for the first time since we started living at the house? Katie said that it's just because they're required to maintain the property, and it just so happens that this was the week they had planned to do it anyway, and the fact that we were just out there is simply coincidence. I suspect otherwise, however. What I think is that one of our neighbors saw us working out there, making a crap job of things, called the Board of Education and told them to have mercy on us and take matters into their own hands. I'm sure if any one of our neighbors did see us out there, it would have been quite the strange sight: two do-it-yourselfers, two foreign do-it-yourselfers, no less, practicing lawn maintenance in a country where practically no one has a lawn.

As an aside, I'd like to note that some of our neighbors have absolutely beautiful topiaries in front of their houses - immaculately trimmed hedges fashioned into elaborate shapes, bonsai trees, bushes and shrubs pruned just so, so that they would grow in the most aesthetically pleasing way. As I understand it, no one does this themselves - they hire professional landscapers. I'm not quite sure how expensive it is, but damn...I want a beautiful Japanese topiary, consarn it!

Anyway, I should also mention our garden. I'd mentioned our garden in a previous post, but I thought I'd provide a quick update on its progress. We have, now, tiny tomatoes! The plants look healthy, though we think they're in need of some pruning now. The two mature basils we bought and the mint are thriving. We threw down a ton of basil seeds once we learned that basil doesn't need to be spaced but a few centimeters apart, and now tiny little tops are peeking out of the ground. Soon, we'll have more basil than we know what to do with, which means a lot of pesto, bruscetta, and caprese. As for the bell peppers, well, I'm not quite sure. They look healthy, and they're budding, but I'm not sure what's going on there - maybe they take a long time to grow. Who knows? Still, Katie and I are very excited; it's so rewarding growing your own food.

Until next time,

-Robert

So I get to school on Monday, at which time I'm informed that the school will be sending someone to our house on Thursday to cut our grass (the Hyogo Prefectural Board of Education owns the property and is responsible for maintaining it, although Katie and I always try to fix small problems ourselves). What luck! Just after we (mostly) finished doing that very thing ourselves, as best we could at least, given the tools we had to do the job. So now we get a professional - hurray! I can only wonder, though; is this just a coincidence? Why would the school pick this week to do some lawn maintenance, immediately after we tried doing the same for the first time since we started living at the house? Katie said that it's just because they're required to maintain the property, and it just so happens that this was the week they had planned to do it anyway, and the fact that we were just out there is simply coincidence. I suspect otherwise, however. What I think is that one of our neighbors saw us working out there, making a crap job of things, called the Board of Education and told them to have mercy on us and take matters into their own hands. I'm sure if any one of our neighbors did see us out there, it would have been quite the strange sight: two do-it-yourselfers, two foreign do-it-yourselfers, no less, practicing lawn maintenance in a country where practically no one has a lawn.