Have you read Barbara Kingsolver's new book, Animal, Vegetable, Miracle? If you haven't, go read it. NOW.

You're back? Good. I would be a little ashamed to tell you just how much I learned from that book. I should have known, for instance, how potatoes grow, or how to store things like tomatoes and zucchini when the season is over. (Just freeze them whole, apparently.) Thanks to a summer working in a grocery store, I know when the different summer crops come into season, and how to pick the best fruits or vegetables off the store shelf. Even cantaloupes. And since starting our little garden out back, I've learned quite a lot more. I thought that if I had to start producing a majority of my own food, I could do it. That's what Kingsolver and her family did, for a whole year. The premise appealed to me (though I'm certainly not going to try it anytime soon, my backyard isn't that big) from a gardener's standpoint. Since moving to Japan, I've become interested in growing my own food, since I have the space to do it, it's cheaper, and it's healthier (I don't use pesticides.) I started off with some tomatoes, recalling summers at home spent eating delicious homegrown tomatoes. I added bell peppers, which tend to be expensive here. It snowballed from there. For the winter, we're planting onions, garlic, potatoes, and spinach. Now it's less about the money aspect- I can afford all the onions and potatoes I want. It's more about having that homegrown taste, and lessening my impact on the environment.

I've started reading labels in the grocery store on almost every item I buy. I bought lemons last week. There were two types; each cost about $1. One was imported from Chile, the other two prefectures away in Hiroshima. I don't have any statistics for you, but just think about it: how much fuel did it take to get that fresh lemon from Chile to Japan, keeping it cold the whole way? And how much fuel did it require to get from Hiroshima to my street (a distance of, I don't know, about 150 miles.) It's obvious which choice is better for the environment. I'm not sure why everyone isn't complaining about this, since we sure do enough complaining when it comes to filling up our gas tanks. And we're paying for it- if you're not paying for it at the cash register, you're paying when you pay your taxes, since farms (of any size, I believe) can deduct their transportation expenses. The average item on your grocery store shelf probably traveled farther than you did on your summer vacation this year, according to Animal, Vegetable, Miracle.

The other amazing thing to me is that these lemons cost EXACTLY the same amount, despite the wide difference in cost in getting to my local MaxValu. So which farmer will be getting more of my money? Guess. Which lemon did I buy? That's right.

Being in Japan has made me more aware of things like seasonality and local crops. While the Japanese, like Americans, enjoy the luxury of having everything, all the time, for the most part foods are enjoyed only when they're in season. I have recipe cards that tell me what season I should cook each dish in. At first I thought it was silly, I had a mentality of "I can eat onion soup whenever I want!" and so on. But it makes sense, considering our living situation. In February, no Japanese person would say "Oh, I just want something light tonight, like a salad" and then complain about being cold and turn up the heat to 80 degrees. Because you can't. It is 40 degrees indoors, there is no central heat, and if you don't plan on freezing while you sleep, you had better eat some stew for dinner. I'm not saying it's perfect. If I had the choice, I'd go for the central heat, without a doubt. But I'd make sure to eat lots of stew and take lots of baths in the winter, to save some money and help the environment too.

The Japanese also firmly believe in local specialties, another concept I thought was dumb at first. Just about every city has something they are famous for. A city near me, Akashi, is famous for its particular style of grilled octopus balls (they dip them in broth) and there are countless different types of noodles. Every bag of rice is clearly labeled with its area of origin. People travel to Hokkaido just to try the fresh crabs. To me, it seemed silly, because couldn't anyone make some broth for their octopus balls? Well, they could, but Akasahi is on the Japanese Inland Sea, and they probably use some sort of local seaweed that tastes different from the seaweed that grows near Okinawa or Tokyo. It's widely accepted that wines grown in different regions or even different counties will taste different. Why not food? When I ate crab in Hokkaido this summer, it tasted fresher than any other crab I've had here. There's no substitute for it. When I returned from Hokkaido, my coworker asked me these questions, in order:

Her: Welcome back! Did you have a good trip?

Me: Yes, it was very relaxing.

Her: Did you eat jingus kan? (grilled mutton on sticks, a famous Sapporo dish)

Me: No, but I ate a lot of ramen. (Sapporo is also famous for its style of ramen.)

Her: How about crab?

And so on. And don't forget the number one most important thing of Japanese vacations-- you must bring back o-miyage, or souvenirs. This is ALWAYS food. The idea is that you should bring back some local food for all your coworkers to sample. From various vacations, I have brought back chocolates, chips made out of bitter gourds, fruit-flavored cookies, tofu cookies, bean-filled dumplings, buckwheat pancakes, and so on.

I think that if Barbara Kingsolver were to come to Japan, she would be disappointed that Japanese mothers do not "take the time to roll out the sushi by hand," as she suggests in her book. The only people I know who make sushi are sushi chefs, and no, even in Japan, there is no such thing as a "sushi machine." But she would be pleased to find a- dare I say it?- UNIQUE food culture that is built entirely upon eating local food, in season.

Wednesday, September 10, 2008

Thursday, July 31, 2008

Japan: Year One

On Tuesday of next week, it will have been one year since I first set foot in the Land of the Rising Sun. I wanted to take this opportunity to reflect a little bit on the experience and how it's changed me and the way I see the world, in part to convince myself that I'm not wasting my time here.

The most obvious thing that comes to mind is that I'm better on a bike now than at any other point in my life. Even when I was really young, like 10 years old, and the bike was my primary means of transportation, I couldn't do all the cool things my friends could do, like ride with no hands. Now, I'm proud to say that not only can I ride a bike with no hands, but also while holding an umbrella, texting on a cell phone, and avoiding old ladies who don't bother to look when they step out onto the sidewalk directly into my path.

The second is that while I'm by no means proud of my Japanese, I speak considerably more than I did when I came. And I can understand far more than I can speak, as I'm sure is often the case. My main regret is that I didn't start seriously studying the language sooner, so I wasted a lot of time trying to absorb Japanese through osmosis when I could have been going to my Kumon/conversation lessons every week from Day 1. Unfortunately, Japanese isn't quite like Spanish or Italian, which people living in those countries tend to "pick up" after spending a certain amount of time there, and it takes considerably more time to become proficient if you don't start hitting the books right away. Indeed, the only foreigners I know who have excellent Japanese either 1.) studied it previously in college, or 2.) have simply lived here for a long, long time. Since neither is true in my case, I should have been more serious about learning the language from the beginning. But hindsight is always 20/20, as they say, and I'll just have to work doubly hard from now on to catch up.

The third thing is that I'm much more aware of the seasons. This mostly has to do with the fact that you're exposed to the weather to a greater extent than back home. The lack of insulation or central air and heating means that you're hotter in the summer and colder in the winter, which of course is the natural order of things. This stands in direct contrast to America, where we frequently turn up the a/c so much during the summer that we have to put on jackets while indoors. Also, certain fruits and vegetables, as well as certain items on restaurant menus, are only available during specific times of the year. Now I know, for example, when eggplants are cheapest, when not to buy grapes, and when nabe will be widely available at restaurants.

Fourth is that Katie and I have made quite a few friends in a year, both foreign and Japanese. We didn't really start hanging out with the local kids in earnest until this spring, so we missed out on a lot of good times. Now she and I are more socially involved and we frequently find ourselves booked solid the entire weekend (and often during the week when we have no previous plans). This has been the most welcome change from how we spent the majority of our time at the beginning of the year.

Fifth is that I've managed to do quite a bit of traveling in the last year. Domestically, I visited many places and got to see quite a bit of the western part of Japan. I was also able to visit Korea, Malaysia, and Singapore: three places I never thought I'd ever be able to visit, but which living in Japan has made accessible and convenient. This summer Katie and I are going to Hokkaido with her family as well as to Vietnam, so opportunities to get out and see the world continue to appear, though with gas prices being what they are, such opportunities are getting pricier. Hopefully it won't prove too detrimental to our insatiable wanderlust and we'll be just as active in the coming year as we were in the past one.

Sixth is that I've been able to save a substantial amount of money. With little in the way of expenses, and with no debt between us, both she and I are making the most of our situation. I need to become more financially savvy, as right now most of my money's sitting in a Japanese bank accruing very little in the way of interest. That will be one of my goals for the coming year.

Seventh is how I've changed physically. I'm now a morning person, and I can't seem to sleep past 8 AM anymore even if I try. Katie and I often cook for ourselves using fresh ingredients, so we tend to eat well. We also go for a morning run three times a week, which combined with my twice-daily 40 minute commute by bike, has served to whip me into half-decent shape (though the daily biking has given me quite the embarrassing farmer's tan). The other weekend I found myself spending Saturday climbing up approximately 1400 steps - the equivalent of a 70 storey building - to visit a shrine, only to spend the next two days cycling 75 kilometers across an island chain in the Inland Sea. A year ago, if you told me I'd do something like that, I'd ask you what you were smoking, and if you could bear to part with any. There's so much to do in Japan in the way of outdoor activities - hiking, skiing, etc. - that you're really doing yourself a disservice if you stay cooped up all the time.

There are plenty more to mention, but since seven's a nice number, I'll stop there. I'm definitely looking forward to seeing what this next year in Japan has in store. Whatever happens, it certainly won't be boring.

-Bob

The most obvious thing that comes to mind is that I'm better on a bike now than at any other point in my life. Even when I was really young, like 10 years old, and the bike was my primary means of transportation, I couldn't do all the cool things my friends could do, like ride with no hands. Now, I'm proud to say that not only can I ride a bike with no hands, but also while holding an umbrella, texting on a cell phone, and avoiding old ladies who don't bother to look when they step out onto the sidewalk directly into my path.

The second is that while I'm by no means proud of my Japanese, I speak considerably more than I did when I came. And I can understand far more than I can speak, as I'm sure is often the case. My main regret is that I didn't start seriously studying the language sooner, so I wasted a lot of time trying to absorb Japanese through osmosis when I could have been going to my Kumon/conversation lessons every week from Day 1. Unfortunately, Japanese isn't quite like Spanish or Italian, which people living in those countries tend to "pick up" after spending a certain amount of time there, and it takes considerably more time to become proficient if you don't start hitting the books right away. Indeed, the only foreigners I know who have excellent Japanese either 1.) studied it previously in college, or 2.) have simply lived here for a long, long time. Since neither is true in my case, I should have been more serious about learning the language from the beginning. But hindsight is always 20/20, as they say, and I'll just have to work doubly hard from now on to catch up.

The third thing is that I'm much more aware of the seasons. This mostly has to do with the fact that you're exposed to the weather to a greater extent than back home. The lack of insulation or central air and heating means that you're hotter in the summer and colder in the winter, which of course is the natural order of things. This stands in direct contrast to America, where we frequently turn up the a/c so much during the summer that we have to put on jackets while indoors. Also, certain fruits and vegetables, as well as certain items on restaurant menus, are only available during specific times of the year. Now I know, for example, when eggplants are cheapest, when not to buy grapes, and when nabe will be widely available at restaurants.

Fourth is that Katie and I have made quite a few friends in a year, both foreign and Japanese. We didn't really start hanging out with the local kids in earnest until this spring, so we missed out on a lot of good times. Now she and I are more socially involved and we frequently find ourselves booked solid the entire weekend (and often during the week when we have no previous plans). This has been the most welcome change from how we spent the majority of our time at the beginning of the year.

Fifth is that I've managed to do quite a bit of traveling in the last year. Domestically, I visited many places and got to see quite a bit of the western part of Japan. I was also able to visit Korea, Malaysia, and Singapore: three places I never thought I'd ever be able to visit, but which living in Japan has made accessible and convenient. This summer Katie and I are going to Hokkaido with her family as well as to Vietnam, so opportunities to get out and see the world continue to appear, though with gas prices being what they are, such opportunities are getting pricier. Hopefully it won't prove too detrimental to our insatiable wanderlust and we'll be just as active in the coming year as we were in the past one.

Sixth is that I've been able to save a substantial amount of money. With little in the way of expenses, and with no debt between us, both she and I are making the most of our situation. I need to become more financially savvy, as right now most of my money's sitting in a Japanese bank accruing very little in the way of interest. That will be one of my goals for the coming year.

Seventh is how I've changed physically. I'm now a morning person, and I can't seem to sleep past 8 AM anymore even if I try. Katie and I often cook for ourselves using fresh ingredients, so we tend to eat well. We also go for a morning run three times a week, which combined with my twice-daily 40 minute commute by bike, has served to whip me into half-decent shape (though the daily biking has given me quite the embarrassing farmer's tan). The other weekend I found myself spending Saturday climbing up approximately 1400 steps - the equivalent of a 70 storey building - to visit a shrine, only to spend the next two days cycling 75 kilometers across an island chain in the Inland Sea. A year ago, if you told me I'd do something like that, I'd ask you what you were smoking, and if you could bear to part with any. There's so much to do in Japan in the way of outdoor activities - hiking, skiing, etc. - that you're really doing yourself a disservice if you stay cooped up all the time.

There are plenty more to mention, but since seven's a nice number, I'll stop there. I'm definitely looking forward to seeing what this next year in Japan has in store. Whatever happens, it certainly won't be boring.

-Bob

Sunday, July 20, 2008

Moderation

Some Japanese people react very strangely to summertime. There are two major types of people (and I see them on a daily basis):

The first type is the ganguro girls, who look somewhat like a stereotypical California girl. They are not American. They are Japanese. Somehow they have convinced themselves if they grow their hair very long and then bleach, and perm and tease it, it will look like they have naturally curly blond hair. Actually, when you perm and bleach fine, straight black hair, it turns out an orange mess. They also tan excessively so their skin kind of matches their hair. They wear shorts that are about the length from my outstretched thumb to my pointer finger. Their shoes are about that same height. The strangest part is that they put white eyeliner all around their eyes and sometimes down the middle of their nose. In the summer they like to hang out at the beach, wearing bikinis with lots of extra padding on the chest, where they can get their photo taken by creepy middle aged men who walk around the beach with giant cameras and photograph any mildly attractive girl.

The second I like to call the beekeepers. These are women, usually aged 30 and above, who are petrified of getting a suntan. Most women in East Asia dislike suntans because it looks like they've been out working in the sun or something else low-class. Elbow length gloves or long sleeves are de rigeur, even when it's 100 degrees out. The grandmas are the most extreme. When I go jogging at 6:30 am, I often see lots of older people out exercising. The women wear long sleeves or long gloves with their short sleeves, and a hat. The really hardcore ones wear long pants and long sleeves, with gloves, of course. They put a towel on their heads (covers the back of the neck) and put a hat (very long brim, naturally) on top of that. Then they pull the ends of the towel around to the front of their face and clip it with a clothespin. Now it's time to go for a walk! At 6:30 am there is no way there is enough UV to change your skin color. They literally look like they were taking care of their bees, and then suddenly decided to go exercise. That's how much skin is exposed. I think perhaps the Taliban was more lenient, I think during their regime you could at least show your hands as well as your eyes.

I'm not sure who scares me more.

The first type is the ganguro girls, who look somewhat like a stereotypical California girl. They are not American. They are Japanese. Somehow they have convinced themselves if they grow their hair very long and then bleach, and perm and tease it, it will look like they have naturally curly blond hair. Actually, when you perm and bleach fine, straight black hair, it turns out an orange mess. They also tan excessively so their skin kind of matches their hair. They wear shorts that are about the length from my outstretched thumb to my pointer finger. Their shoes are about that same height. The strangest part is that they put white eyeliner all around their eyes and sometimes down the middle of their nose. In the summer they like to hang out at the beach, wearing bikinis with lots of extra padding on the chest, where they can get their photo taken by creepy middle aged men who walk around the beach with giant cameras and photograph any mildly attractive girl.

The second I like to call the beekeepers. These are women, usually aged 30 and above, who are petrified of getting a suntan. Most women in East Asia dislike suntans because it looks like they've been out working in the sun or something else low-class. Elbow length gloves or long sleeves are de rigeur, even when it's 100 degrees out. The grandmas are the most extreme. When I go jogging at 6:30 am, I often see lots of older people out exercising. The women wear long sleeves or long gloves with their short sleeves, and a hat. The really hardcore ones wear long pants and long sleeves, with gloves, of course. They put a towel on their heads (covers the back of the neck) and put a hat (very long brim, naturally) on top of that. Then they pull the ends of the towel around to the front of their face and clip it with a clothespin. Now it's time to go for a walk! At 6:30 am there is no way there is enough UV to change your skin color. They literally look like they were taking care of their bees, and then suddenly decided to go exercise. That's how much skin is exposed. I think perhaps the Taliban was more lenient, I think during their regime you could at least show your hands as well as your eyes.

I'm not sure who scares me more.

Monday, June 16, 2008

Through fresh eyes

After you've been living in a place for a while, you tend to forget the things that shocked or amused you so much when you first arrived. You take for granted the fact that, in Japan anyway, there are cigarette vending machines on every corner. You understand that you don't have to tip at restaurants, and the displayed price for the convenience store candy bar is exactly what you pay at the register - you don't give it a second thought. You think nothing of the teenage kid decked out in his punk-rock finest, hair dyed red, a skull-n-crossbones patch safety pinned to his black bowler hat, strolling arm in arm with a girl in full kimono, a Louis Vuitton clutch dangling at her side. So nothing amuses me more than going to all my favorite locations accompanied by people who are seeing Japan for the first time in their lives through fresh eyes, wide and bright from the adrenaline rush that comes from actually being in a place to which you never thought you'd have the opportunity to travel.

So it was that Katie and I were called upon by our Japanese surrogate parents, the Masaokas (to whom we are indebted forever for all the help they've given us over the past year, not the least of which involved guiding us through the labyrinthine entrails of Japanese hospitals and American insurance companies when Katie had her emergency appendectomy last August), to come to Kyoto Station to meet our predecessors - the people who had my same job and lived in my very house two years ago. We knew precious little about Ned and Megan: they were from Washington State and had translated the menu at the Chinese restaurant next door which we frequent into English. That's about it. So we were excited to meet them and, selfishly, were excited to have any excuse at all to go to Kyoto.

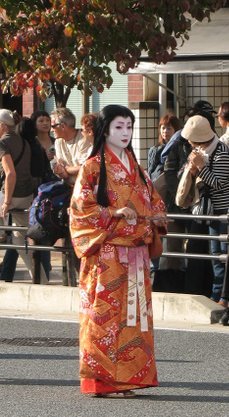

When we got to Kyoto Station (Ned refers to it as the Death Star because it is the largest and most futuristic-looking building you'll ever set foot in), we saw Mr. and Mrs. Masaoka surrounded by a group of foreign kids; they looked like high school students. "Oh no," Katie said, "Mrs. Masaoka found a group of high school kids on a school trip and has probably taken it upon herself to personally show them around for the day." Such behavior would be totally normal for Mrs. Masaoka, which goes to show you the kind of person she is. She was dressed in summer kimono, which we suspect she does for the benefit of the foreigners she meets (when Katie's family came in March she showed up to our house dressed like that, for example). As it turned out though, Megan and Ned are both teachers back in Spokane and Ned had brought along some of the students from his Japanese class - apparently he teaches mainly social studies but also beginning Japanese on the side. So Katie and I go down to meet 12 more people than we had originally expected to, and we didn't quite know what to make of the situation. As it turned out, the kids were all really nice and subdued from the jet lag, so we were mercifully spared the horrific fate of keeping tabs on a bunch of teenagers running amok around the Old Capital.

Ned and Megan were incredibly nice people and a lot of fun to talk to; they knew the area around our house quite well as they had lived there, of course, so we talked about that quite a bit. Ned's students seemed to be quite mature and responsible as it turned out, so Katie and I were able to talk to them and answer their questions about living in Japan. The best part, of course, was just watching their reactions to things we simply take for granted living here: the ubiquitous vending machines, the lack of public trash cans, the fashion, just to name a few. To watch them taking pictures of the most mundane objects and shouting excitedly about stuff you see on your way to work every day energizes you and makes you feel privileged to live here. I often felt the same way when I was working downtown in DC and would walk down Pennsylvania Avenue on my lunch break past the White House, passing groups of tourists pointing and taking pictures. I was so fortunate, I thought, to live in such a place. I've no doubt my friends currently scattered across the globe experience the same when they spy a group of out-of-towners talking excitedly to each other, bedecked in backpacks and walking shoes, cameras at the ready, able to see things they'd long since forgotten through fresh eyes.

So it was that Katie and I were called upon by our Japanese surrogate parents, the Masaokas (to whom we are indebted forever for all the help they've given us over the past year, not the least of which involved guiding us through the labyrinthine entrails of Japanese hospitals and American insurance companies when Katie had her emergency appendectomy last August), to come to Kyoto Station to meet our predecessors - the people who had my same job and lived in my very house two years ago. We knew precious little about Ned and Megan: they were from Washington State and had translated the menu at the Chinese restaurant next door which we frequent into English. That's about it. So we were excited to meet them and, selfishly, were excited to have any excuse at all to go to Kyoto.

When we got to Kyoto Station (Ned refers to it as the Death Star because it is the largest and most futuristic-looking building you'll ever set foot in), we saw Mr. and Mrs. Masaoka surrounded by a group of foreign kids; they looked like high school students. "Oh no," Katie said, "Mrs. Masaoka found a group of high school kids on a school trip and has probably taken it upon herself to personally show them around for the day." Such behavior would be totally normal for Mrs. Masaoka, which goes to show you the kind of person she is. She was dressed in summer kimono, which we suspect she does for the benefit of the foreigners she meets (when Katie's family came in March she showed up to our house dressed like that, for example). As it turned out though, Megan and Ned are both teachers back in Spokane and Ned had brought along some of the students from his Japanese class - apparently he teaches mainly social studies but also beginning Japanese on the side. So Katie and I go down to meet 12 more people than we had originally expected to, and we didn't quite know what to make of the situation. As it turned out, the kids were all really nice and subdued from the jet lag, so we were mercifully spared the horrific fate of keeping tabs on a bunch of teenagers running amok around the Old Capital.

Ned and Megan were incredibly nice people and a lot of fun to talk to; they knew the area around our house quite well as they had lived there, of course, so we talked about that quite a bit. Ned's students seemed to be quite mature and responsible as it turned out, so Katie and I were able to talk to them and answer their questions about living in Japan. The best part, of course, was just watching their reactions to things we simply take for granted living here: the ubiquitous vending machines, the lack of public trash cans, the fashion, just to name a few. To watch them taking pictures of the most mundane objects and shouting excitedly about stuff you see on your way to work every day energizes you and makes you feel privileged to live here. I often felt the same way when I was working downtown in DC and would walk down Pennsylvania Avenue on my lunch break past the White House, passing groups of tourists pointing and taking pictures. I was so fortunate, I thought, to live in such a place. I've no doubt my friends currently scattered across the globe experience the same when they spy a group of out-of-towners talking excitedly to each other, bedecked in backpacks and walking shoes, cameras at the ready, able to see things they'd long since forgotten through fresh eyes.

Monday, June 9, 2008

Update 6/9

Well, yet another week begins, with Monday and Tuesday leaving me very little to do aside from my Japanese lessons. This past weekend was a lot of fun: on Saturday we had some of our new Japanese friends over for Korean food. One of them brought her 5 year-old daughter who's enrolled at a local international school and thus speaks English relatively well. We taught her how to play Life (the board game), the Japanese version of which Katie found at the local recycle shop for a measly 300 yen. For dinner we made sam gyeop sal, or barbecued pork grilled alongside various toppings which you then roll into a sesame leaf and eat with your hands. It tasted exactly the same as what we ate in Busan, which pleased us - and our tummies - greatly.

Sunday I really wanted to get out of the house, having spent Saturday cleaning up, going grocery shopping, and helping to prepare dinner. Katie and I decided to go to the Osaka aquarium, which we had heard was a great way to spend an afternoon. After the obligatory Sunday breakfast of blueberry pancakes (the packet of frozen blueberries we bought at Costco several months ago are still going strong), Katie tended the garden for a bit, then we headed downtown. Admission to the aquarium was outrageously expensive, so we decided to buy a day pass which, in addition to covering the aquarium's entrance fee, would allow us to ride the subway as much as we wanted for free. The aquarium itself looks like a giant modern art installation, sitting on Osaka Bay. Inside we saw all kinds of fish in an incredible array of sizes, shapes, and terrifying-ness. The main attraction is the whale shark which easily dwarfs the next biggest fish in the entire aquarium several times over. The best part of the whole thing, though, wasn't what lives in the water, but what spends most of its time above it. Katie and I spent a lot of time at the otter, penguin, seal, and sealion tanks. It helps that those animals are the cutest ones, but there you are.

After the aquarium we rode the subway to Shinsaibashi in South Osaka to eat at an Ethiopian restaurant we had heard about. It was expensive (and we were the only ones eating there, which worried me a little), but the food was so damn good. It made me miss Mesob in Charlottesville so much, and filled me with regret for all of the great Ethiopian restaurants in DC I neglected to try when I lived so nearby. At the bar sat two barrel-chested and bearded Ethopian fellows - I could tell they were authentically Ethiopian because of their narrow-bridged noses. Otherwise, it would be safe to assume they were Nigerian, since those are really the only black people you see in Japan on a regular basis. They spoke a bizarre pidgin of English and Japanese, and chatted away over their beers unperturbed by the conspicuous lack of customers on a Sunday evening. Sometimes Katie and I wonder how it is that these places we love - a Vietnamese hole-in-the-wall in Nishinomiya, a pizzeria in Osaka that serves up pizzas blessedly unadorned with creative Japanese topping like corn and mayonnaise, any number of Turkish restaurants in Kobe, etc. - manage to stay in business when we seem to be the only ones patronizing them. I like to think they're all fronts for the Yakuza.

After the aquarium we rode the subway to Shinsaibashi in South Osaka to eat at an Ethiopian restaurant we had heard about. It was expensive (and we were the only ones eating there, which worried me a little), but the food was so damn good. It made me miss Mesob in Charlottesville so much, and filled me with regret for all of the great Ethiopian restaurants in DC I neglected to try when I lived so nearby. At the bar sat two barrel-chested and bearded Ethopian fellows - I could tell they were authentically Ethiopian because of their narrow-bridged noses. Otherwise, it would be safe to assume they were Nigerian, since those are really the only black people you see in Japan on a regular basis. They spoke a bizarre pidgin of English and Japanese, and chatted away over their beers unperturbed by the conspicuous lack of customers on a Sunday evening. Sometimes Katie and I wonder how it is that these places we love - a Vietnamese hole-in-the-wall in Nishinomiya, a pizzeria in Osaka that serves up pizzas blessedly unadorned with creative Japanese topping like corn and mayonnaise, any number of Turkish restaurants in Kobe, etc. - manage to stay in business when we seem to be the only ones patronizing them. I like to think they're all fronts for the Yakuza.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)